Thursday, June 6, 2019

Wednesday, June 5, 2019

GPU path tracer, pt 2: spectral path tracing

I was quite unhappy with the performance of my previous GPU path tracer, so I started a new path tracer, this time forked off the work I did for my master's thesis research. Due to better architecture, newer hardware and an updated version of Optix Prime, I managed to improve the performance by almost tenfold over my previous work, at least in more complex scenes. A streamlined architecture where everything runs from a single kernel reduces the memory bandwidth use significantly, as I no longer need to load path data multiple times for a single path extension call. This means I can render images such as this one in less than an hour:

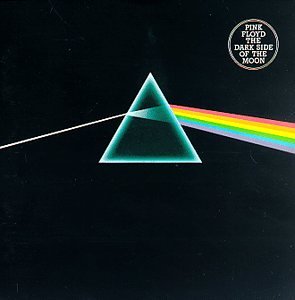

With the significant increase in performance, I wanted to try something I've always thought would be really cool, but never really ended up doing due to the images requiring massive amounts of samples to look good. Spectral path tracing means that paths carry 'photons' of a single wavelength, rather than some abstract distribution represented by an RGB color triplet. This allows effects such as diffraction at material interfaces, which results in the prism effect familiar from many high school physics classes:

Replicating this with a forward path tracer turned out to be quite difficult though. Finding a path that actually carries light through a prism turned out to be really unlikely for a collimated beam of light, so I had to resort to a slightly blurred version like this:

Clearly forward path tracing is not the way to go for rendering coherent beams of light. Therefore I modified the path tracer to also support light tracing. While my implementation is not totally unbiased, it seems to only be off by some missing constant factor, thus letting me render nice pictures. A few good ones are shown below:

A scene with complex refractions and caustics, requiring 16 indirect bounces. 21 thousand samples per pixel are rendered in roughly 40 minutes, resulting in an almost noiseless image.

With the significant increase in performance, I wanted to try something I've always thought would be really cool, but never really ended up doing due to the images requiring massive amounts of samples to look good. Spectral path tracing means that paths carry 'photons' of a single wavelength, rather than some abstract distribution represented by an RGB color triplet. This allows effects such as diffraction at material interfaces, which results in the prism effect familiar from many high school physics classes:

Replicating this with a forward path tracer turned out to be quite difficult though. Finding a path that actually carries light through a prism turned out to be really unlikely for a collimated beam of light, so I had to resort to a slightly blurred version like this:

A conical light beam seen through a refractive prism. This took almost 1 million samples per pixel and 8 hours to render, and is still visibly noisy.

A collimated light source interacting with two prisms.

A complex scene displaying caustics from multiple collimated light sources.

Space Combat Warfare, pt 3: Orbit simulator

A good space war game requires orbital maneuvering to really feel realistic. That's why I built this orbital simulator as a fork of my main game project a while ago. Source code of the forked game can be found here: https://vollikainen.visualstudio.com/_git/spess%20program

Even with only a few planets and one ship, things get tricky quite quickly since I want to be able to compute new orbits for ships in real time. Due to that, I had to separate the orbit computation of planets and ships so that I only need to compute a new orbit for the ship when it maneuvers, not the whole solar system. As an example, here are orbits for all planets up to Jupiter, simulated over two years:

Even with only a few planets and one ship, things get tricky quite quickly since I want to be able to compute new orbits for ships in real time. Due to that, I had to separate the orbit computation of planets and ships so that I only need to compute a new orbit for the ship when it maneuvers, not the whole solar system. As an example, here are orbits for all planets up to Jupiter, simulated over two years:

Pictured: a two-year simulation of the inner planets and Jupiter, computed in 60 ms.

As you can see, Jupiter only does about 1/5th of an orbit in the allotted time frame. This means I must be able to simulate planet trajectories over extremely long time frames, and then caching the results so I can compute arbitrary orbits for the ship in the whole solar system. This means that our orbit computation algorithm has to be highly optimized, otherwise computing the effect of any maneuver of the ship could end up taking seconds of computing time, rendering the simulator extremely hard to use.

One essential improvement that allows for quicker orbit computations is a good numerical integrator for the orbits. I want something that allows me to use longer time steps without incurring a lot of error. A runge-kutta 4 integrator is a good enough solution for that. It's simple to implement and gives good accuracy and is fast to compute too. Additionally, I want to use an adaptive time step so that I don't need to manually adjust it all the time. I simply select a level of accuracy required of the simulator and let the algorithm figure out how to get that. This lets me compute orbits such as in the image below in real time:

A flyby of the Moon with a free return trajectory. The ship's trajectory is shown in green, with the Moon insertion burn highlighted in red. Due to the shape of our orbit, we can return to Earth without having to use our thrusters in Lunar orbit at all. The 8-day orbit is computed in 4 ms, allowing for comfortable real-time editing.

Running both the planets and the ship trajectories on different time steps due to the adaptive integration presents a new problem: When computing a ship's trajectory, the time resolution is different than for the planetary simulation. This means we must have some kind of interpolation system for planet positions. A simple linear approximation would work, but it would not be a good one since orbits never follow linear trajectories, meaning I'd have to increase the time resolution of the planet simulation to keep interpolation errors acceptable, so that's out of the question.

Instead, I chose to use splines to approximate a planet's trajectory and use it to compute the planet's state between exact known states. As a third-order approximation, it is a good approximation of a planet's behaviour over short time periods at least, and that's really all we need. Due to the adaptive nature of my integrator, the difference between two consecutive time steps should be minor, meaning we should not get a whole lot of error in the interpolation. Using linear least squares to fit a spline to the planet's trajectory gives us a good approximation, as shown in the video below:

This video shows a spline being fitted to a planet's trajectory. To really show the approximation errors, the time period used for the fit is increased greatly. Here we fit the spline to 100 consecutive states of the planets, when in real use cases it would only be necessary to fit to 4-6 states.

All of these optimizations combined give me a robust orbit simulator that can simulate almost any trajectory in real-time, if not always at an optimal refresh rate. Here are some example videos showing how smooth the trajectory planning is, compute time wise. The UI is quite terrible for now, but that's an issue for another time.

This video shows a transfer from Earth orbit to a circular orbit over the Moon.

And this one shows an interplanetary transfer from Earth orbit to Mars, with a gravity assist from the Moon.

Tuesday, June 4, 2019

Space Combat Warfare, pt2: Ship AI

My ship model allows for thrusters to be placed on any point on a ship, rotated at any angle. This presents some interesting issues for designing an AI that can steer the ship using those thrusters in a newtonian simulation. Non-symmetric thruster setups mean that a naive solution will just end up driving in a circle due to rotation forces caused by the center of thrust not being located at the ship's center of mass. Therefore a smarter steering AI that can balance an arbitrary thruster configuration is required:

Here's a video showing the steering AI in action. The steering AI is told to stop a ship that is moving vertically. The ship's thrusters are placed the same way every time, but the thrusters are rotated randomly between runs. This is a good test case, since the AI can't make any assumptions about the usable direction of thrust or the thrusters being balanced in a given way.

The AI works by first finding the vector of maximum acceleration for a ship, pointing the ship in that direction, then firing thrusters in a configuration that will result in translational acceleration while maintaining the rotational acceleration at zero. Note also how the turning AI optimizes for propellant use while turning by only using the thrusters that cause the most rotational acceleration per unit of thrust applied.

This kind of highly adaptive AI is necessary even for ships that don't have their thrusters placed at random angles. Since our ships can be damaged, that means a ship can lose thrusters that are vital to its steering, and a less general AI would lose control of the ship far faster than necessary. This AI can easily adapt to destroyed thrusters, as shown in the following video:

Here the AI is told to maintain maximal thrust towards the left, while keeping the ship's rotation velocity at 0. Destroying the engines will not stop the AI from steering towards the target until there are no possible thrust configurations that would result in an out of control spin. This means that as long as any two thrusters' thrust axes are located in different sides of the center of mass, the ship can steer succesfully.

This physically correct model of thrusters causes some issues for trajectory design too. Traveling from point A to point B becomes a complicated problem when you need to account for ship turning times and allow some errors in the steering AI to be corrected. Here's a video showing a ship traveling on AI control to points the player clicks on the map:

Note how the ship has a difficult time at pointing its thrusters to the designed direction, and it ends up making a slight error in the resulting burn vector. This is caused by the turning thrusters imparting a linear acceleration on the ship, which slightly changes the required burn vector. This ends up in a feedback loop that needs to be accounted for by adding some safety margins into the steering AI, so that it doesn't even try to do 100% perfect burns. Instead, it's content with accelerating in almost the correct direction and continuously correcting the angle of acceleration during the acceleration burn.

Finally, here's a video showing a ship traveling to a point 10 kilometers away. It's acceleration is 20 m/s^2, so the optimal time for this trip, including a braking burn, is roughly 45 seconds. My steering AI manages to do it in 63 seconds including some overhead due to the roll to point the main thrusters backwards halfway through the trip, so it gets quite close to an optimal travel time.

Space Combat Warfare, pt 1: damage mechanics

I started another space combat game project in an attempt to create an even more detailed simulation of the various effects found in space warfare. This time I had no intentions to ever finish the project, its goal was more just testing my hand at writing a high-quality real-time simulation. Ships are assembled from blocks, which in turn consist of a grid of mass elements that run a detailed temperature and ballistic simulation. Source code for the project can be found here: https://vollikainen.visualstudio.com/_git/space%20combat%20warfare

A video demonstrating hypervelocity (10 km/s) rounds impacting a ship's steel armor. The projectile is so fast that it essentially explodes on contact with the armor, scattering shrapnel in all directions.

Here is a test of a whipple shield design, where thin Aluminium plates separated by vacuum are able to stop a large projectile impacting the armor at a massive velocity. The projectile is vaporized on impact with the first plate, and the following plates are able to stop the resulting high-velocity shrapnel due to the projectile's energy spreading over a large surface area thanks to spacing between armor plates.

Here's a video demonstrating the lasing and heat mechanics. On the left a transparent armor plate made out of diamond is able to resist ablation from the laser due to its excellent heat conduction and transparency spreading absorbed energy over a large area. The larger block is made out of aluminium and has no such advantages, so it is quickly ablated despite part of the beam's energy being absorbed by the diamond plate. The mass grid's temperature is visualized in false color to better display the heat transport mechanics in action.

Finally here's a full ship model being impacted repeatedly by railgun projectiles. The armor is again a whipple shield layout, with an outer aluminium plate backed by a pressure plate made out of tungsten. The ship's hull is made out of softer polyethylene plastic, so it is very weak to direct hits from the projectiles. Even though the armor can't stop the impacts completely, it is strong enough to vaporize the projectile and therefore limit and spread the damage to the ship's hull over a larger area. You can see a drastic difference when a projectile hits the hull directly, creating a huge crater in it.

GPU path tracer

For my bachelor's thesis I wrote an implementation of gradient-domain path tracing on the GPU. After it was done, I repurposed the path tracer into a hobby project, implementing all kinds of fun effects into it. It's written in CUDA and runs completely on the GPU. For ray-scene intersections I used Optix Prime, everything else runs on my own code. The performance ended up being fairly poor due to my inexperience with working on GPU programming. I would eventually correct those issues for my master's thesis work though.

I ended up with support for depth of field, multiple importance sampled emissive light sources and glossy materials, refractions and scenes composited from multiple objects. Here are a few images I saved over the course of that work.

I ended up with support for depth of field, multiple importance sampled emissive light sources and glossy materials, refractions and scenes composited from multiple objects. Here are a few images I saved over the course of that work.

This image shows normal mapping in action. The wall geometry is just two triangles, all the detail comes from normal maps as well as diffuse and specular textures.

Here's another image with normal maps in the crytek sponza scene. This one also features a skylight to simulate a daylight scene.

Here's an image showing polygonal bokeh for depth of field, simulating a hexagonal aperture due to partially closed aperture blades.

A multi-object scene with glass materials and depth of field.

SpaceDM - space combat game

SpaceDM was a game project I worked on with two friends from 2014 onwards. The goal was to make a finely simulated space combat RTS game where everything is based on highly detailed rigidbody physics. Ships are constructed out of small square blocks that can each be destroyed or become separated from the ship. This results in a complex damage model that allows for a wide variety of combat options, ranging from high-velocity cannons to small drones loaded with explosives that attempt to ram enemy ships.

The game is written in C#, and uses .Net framework and OpenTK to handle window creation and interfacing with the OS, but pretty much everything else was made by us. It even had somewhat working multiplayer with a deterministic lockstep simulation. It was only really deterministic when run on a single thread though, so performance in multiplayer was quite poor. All the rigidbody mechanics and a large portion of the game mechanics were written by me.

The ship simulation was quite detailed, with generators being required to provide power for weapons, fuel tanks that were prone to explosions when damaged needed to run the generators, and a heat transport simulation that meant waste heat from generators and weapons needed to be dealt with. Our lasers did not deal any direct damage on blocks, but simply deposited heat on blocks that were hit. Due to the heat simulation, the deposited heat would conduct deeper into ships and start causing damage when blocks would overheat and start melting. Here's a video demonstrating that on asteroids:

We eventually stopped the project due to technical debt accrued over the years, as well as none of us having no good ideas on how to make it an actual interesting game to play, rather than a sandbox physics simulator.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)